I have family friends who always talk about going to “the cottage” every summer when they were kids. Their family had a vacation spot on a lake in northern Indiana, and they have fond memories of venturing up there each year.

Visiting the family homestead isn’t always so familiar, though. With ancestry travel, we have the chance to explore where our ancestors came from. Some people might even get to meet distant relatives on their trip. These trips are often filled with new experiences that open doors not only to our personal roots, but to entire cultures as well.

We talked with Colorado-natives Bill and Jane Frobose about their travels to connect with family in Germany and Czechia, and their friends Bill (yes, another Bill, of which there are multiple in this tale) and Marily Lane who took the adventure of a lifetime to explore his ancestral homeland of Norway.

Discovery through Heritage Travel

In general terms, heritage tourism is travel with the purpose of exploring your ancestral background. It could take you to a specific city or be a broader exploration of an entire country. You might be looking for long-lost family members, or simply hoping to learn more generally about the traditions and history of a culture.

The Froboses and the Lanes got a little bit of everything along the genealogical tourism spectrum. Here are their stories.

Finding the Frobose family tree

Compared to some, the Froboses had a relatively easy time of their research as they already had family contacts.

“How we found out about (our family) was through my cousin who lived about three or four houses down the street from us when we were growing up,” said Bill. “She found out about the Frobose family and our great-great grandfather who moved from Germany to the U.S., to Ohio.”

They contacted another cousin in Germany whose great-great grandfather had been the brother of Bill’s own great-great grandfather. “We found his phone number and when we were going to Germany, talked to him and his wife. We were going on another trip ourselves and arranged to visit them.”

Before going to Germany though, the Froboses planned to visit Jane’s family in Czechia. Through an unusual chain of events, Jane’s brother and sister-in-law did some house sitting in Prague and found a way to get in touch with family while they were there.

They passed that information on to Jane, which led to a tour of small towns in Germany and Czechia in search of ancestral connections.

Looking for the Lanes

Bill Lane had to do a bit more digging to re-create his family tree, but he did have some records passed down through the generations to get him started. His great grandmother had kept an extensive collection of photographs, newspaper clippings, and other mementos. When she passed away, everything went to his grandmother, and eventually to him in 1975.

Using photographs and obituaries from his relatives’ adopted home state of Minnesota — they immigrated from Norway in the mid-1800s — Bill was able to piece together a family tree.

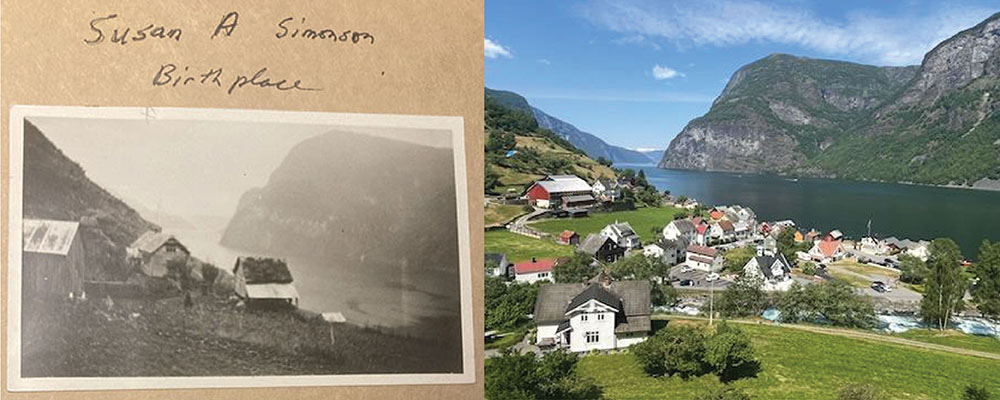

His aunt helped to verify dates, and he turned to the internet, using others’ research and sites like FindAGrave.com, to fill in some of the other gaps. He even matched an old photograph of his great-grandmother’s house, which she hadn’t seen since the age of about five, to the current house in Undredal using nothing but Google Maps.

To say his research was without a few bumps in the road would be oversimplifying the situation. One of Bill’s big challenges was following his family’s name changes.

As is common in more than one Nordic country, last names don’t get passed from parent to child in Norway the same way they do in the United States.

"Say your father’s name is Simon Olsen. Well, your last name isn’t Olsen,” explained Bill. “Your last name is Simonson for a man, or Simonsdottr, usually. Those names aren’t even very consistent.”

Spellings vary greatly, whether it was the spelling of a person’s name — Simonson or Simonsen, for example — or a place name. Plus, people often had “local” names that they may have changed when they moved away from the country. This was the case for Bill’s family.

"If they moved to the city, then they didn’t go by Simonson, because there’s too many Simonsons, so people took on the farm names,” he said, adding that his own family eventually adopted Gjellum, the name of their farm, which has multiple spellings in its own right, for a surname. "And then they come to the U.S., and they start doing, ‘I’m Simon Olsen, but my son won’t be Simonson, he’ll be an Olsen now,’ going to the American style of last names.”

And then on top of it all, Bill isn’t sure where the last name Lane came from, as it seems to have changed arbitrarily from the more Norwegian-sounding Stenson a few generations ago.

The adaptations can admittedly be a double-edged sword. While verifying who is who and whether you’re actually related can be difficult if the names keep changing, adopting place names as family names can also provide clues. For example, Bill was able to find where in Norway distant relations were from by using their farm-based surnames.

Finally, both couples knew where they needed to go, although no one knew exactly what they’d find when their flights touched down.

Meeting Family with the Froboses

By the time the Froboses had landed in Europe, they had already made contact with both Jane’s and Bill’s families. But they kept their hopes in check. It was a vacation for them, but they were entering the real lives of people who, despite being related, were essentially strangers.

“We knew we wanted to meet them, but we weren’t expecting anything. In fact, we were prepared to sleep somewhere else,” said Jane, explaining that some of her family invited them to stay in their home during their visit. “We kind of let them determine what it was they wanted to show us.”

They got to see plenty, and much of it isn’t something the average tourist would get to experience. Bill got to see his family’s home near Menden, Germany.

Bill’s cousin, Wilhelm (yet another “Bill”), showed them around the region, welcoming them for meals, taking them to castles in nearby towns, and being all-around amazing hosts. Among the sites was the original Frobose farm, including the house that had been a gift to Bill’s great-grandfather.

“In addition to that,” said Jane, “they showed us what they believed to be the burial site of his ancestors. The land is so precious for farming that the gravesites are rented for 30 years, and then they can be removed or not. So Wilhelm was saying, ‘We think this is where our ancestors were’ because there’s no more tombstones or anything.”

“The house has been remodeled, obviously, but we got to eat dinner in what would have been the room where my great-great-grandfather was born.”

They also came across a statue of a famous poet in one of the towns they visited. Based on surnames, they believe he may have been a distant relation of Jane’s. “You learn some interesting things about your family’s history,” she said.

For those who haven’t experienced it, genealogical travel — walking into unknown towns and introducing yourself to strangers you’re supposedly related to — can sound rather daunting. Do you just knock on their door with a “Gutentag, you don’t know me, but …"?

Bill and Jane weren’t cold-calling relatives, however, so they had at least a little reassurance they’d be greeted warmly. Just how warmly was a bit of a surprise.

“The interesting thing from both our points of view was that they were humongously happy to visit with us,” Bill said, somewhat in awe. “It was like we had met before, and all of a sudden (we were) hugging each other. It was fantastic.

“Everybody we met on both sides of our family was so pleased to have us there, and they opened their arms and their houses to us.”

Ferrying the Lanes through Remote Norway

Already with a taste for genealogical travel, the Froboses later joined Bill Lane and his wife Marily on a heritage trip to Norway. Unlike his friends, however, Bill didn’t begin his trip with familial contacts or the expectation of meeting relatives. It was simply a 40-year study of his family tree come to life after Marily suggested he finally plan that trip to Norway after COVID.

For starters, Bill had always wanted to take the Hurtigruten ferry. These boats have run up and down the coast of Norway for over a century, taking passengers through the fjords and often to small, remote towns.

Originally, the weekly ferry primarily served local residents, delivering mail and taking people to visit relatives in nearby villages. Today, they run daily and cater more to tourists, providing comfortable cabins and excellent food.

Once he’d booked passage on the ferry, Bill got down to the business of figuring out exactly where his paternal relatives came from.

“My great-grandmother came from a town called Undredal, which is a little village of about 80 people and 500 goats,” he joked.

He isn't wrong, though. The village, which is about a five-hour drive northwest of Oslo, is known for geitost, a brown goat cheese that looks and tastes a bit like caramel. You don’t get that kind of reputation without also having a lot of goats.

“Up above the town up on the hillside, quite a ways up, is a farm that’s called Gjellum Farm,” said Bill of their stop in Undredal. “We actually hiked up there and I had an old photo of the place where she was born, and I could precisely imitate it. We knew we were in the right spot.”

Bill’s great-grandmother had left Gjellum in 1958, at about the age of five, to come to the U.S. She returned in the early 1900s, which is when they took the photograph that proved so helpful for finding his family home.

Bill used an obituary to trace his great-grandfather's lineage back to Ulefoss, Norway, which roughly translates to “howling falls.” It’s aptly named as the region is filled with waterfalls amongst the fjords. The natural scenery, and the waterfalls in particular, turned out to be among the highlights for all four travelers.

"I really didn’t know that they had so many waterfalls. We just saw them over and over and over again. I don’t really care about going to waterfalls in Colorado anymore,” he said, laughing.

“We saw so many really spectacular ones, and they came from huge heights. You could be down there in the fjord on the boat, and you could see this waterfall starting 1,000 feet up, and it’s basically a waterfall all the way down. It’s like a river that’s turned vertical.”

They also traveled a section of the Telemark Canal, built more than a century ago to ease the transport of people and goods between the coast and interior. When the canal and its locks system were completed in 1892, it was dubbed the eighth wonder of the world. The ambitious canal was carved out of the granite cliffs, largely by hand, adding to its impressiveness.

Although Bill wasn’t able to meet any relatives — "these little places they came from were so small, I think the vast majority of people from there had left” — the trip was still full of surprises. From the unexpectedly warm weather despite being above the Arctic Circle to the ways many communities still practice farming with traditional methods to the picturesque views from the ferry and Flåm Railway, the trip could hardly be considered anything but a success.

Advice for Ancestry Travel

What advice do the Froboses have for someone considering a heritage trip? Aside from the research aspect, which can be like going down some never-ending rabbit holes, how to do genealogical travel might be easier than you think.

Here are their top three tips.

1. Learn the language.

Jane recommends the basics — hello, how are you — to show that you’re making an effort with your hosts. “People will just open their arms to you so much more if you take a step to show that you’re opening your heart to them as well.”

2. Travel light.

This is one of Bill Frobose’s favorite tips. First, traveling light means you pack less clothing. Less clothing means you might have to do laundry from the road. And doing laundry in a public laundromat can be a valuable experience.

“Going to a local laundry is an adventure in itself,” he said. “You have to use the local coins in the washer and dryer. Stupid things like that, but it’s a challenge, and it’s really fun to go. You’re going to meet people in a laundry that you would never meet ‘on the street.’”

Second, traveling light gives you room to be spontaneous. While traveling with the Lanes in Norway, having little luggage allowed them all to hop on and off the ferry more freely. If you see a train you want to hop on, even if it’s only stopped in the station for five minutes, you can do that if you aren’t wrestling with several suitcases.

Avoid these overpacking mistakes.

3. Be flexible.

Expect things to be different than you’re used to, and then “go with the flow,” as Jane put it. “If you can go with the flow, it’s amazing how much you’re going to learn.”

Plus, keep in mind that with specialized travel like genealogical trips, flexibility can mean the difference between pursuing a lead in your research and not. You might uncover a relative you’d never heard of or want to visit the family’s remote farmhouse.

Bill Lane booked several of their reservations before departing for Norway — the ferry passage, some hotels — because they weren’t sure what they’d find in these remote areas when they got there. But being too locked into an itinerary when you’re traveling to find the unknown can be quite limiting.

Benefits of Genealogical Travel

First, because your reason for travel may be different than “just” taking a vacation, you’re more likely to get off the beaten tourist trail. This gives you a more local experience and lets you visit cities or regions that fewer tourists visit.

And if you are able to meet with relatives — or any locals — you have an inside guide to everyday life. Talk about an immersive travel experience.

Next, of course, you learn about yourself and your family. For some people, this is extremely emotional and psychologically moving. They may finally be able to answer questions about their identity or connect with family they never had a sense of previously.

It also forces you to examine your own life in a new way. It’s hard to embark on a heritage tour without opening your imagination. What was my family’s life like? What would my own life be like if they had never immigrated? What historical events might they have played a part in? In what ways did they contribute to their community and part of the world?

You may never get concrete answers, but it can be a fun game of what if on your way back home.

“We got to worship in the church of my ancestors,” said Jane of the time they met her father’s side of the family in Czechia. “That was kind of neat to think, ‘Am I sitting in the same pew they might have?’”

Bill Lane had similar reflections, figuring that based on the time his great-grandfather left Norway, it’s possible he and other members of the family worked on the now-famous Telemark Canal.

“I think my great-grandfather took up farming, but he was also a carpenter. He could have been involved (in the canal’s construction). His father would have been in his 30s or 40s at the time the canal was built, so there’s a good chance he would have been involved. There were a lot of people working on it.”

Finally, it helps you to keep your family history alive. All too often, we’re left wishing we’d asked our parents or grandparents more about their lives while we still had the chance. With heritage travel, you can rediscover some of the family lore you might have lost and, perhaps, pass it along to the next generation.

Plan Your Own Ancestry Tour

Ready to start planning your own heritage tour but don’t know where to start? Check out our planning guide to ancestry travel. And don’t forget to sign up for The Wayfinder, expert travel tips delivered to your inbox once a month.

Travel Like a Pro with The Wayfinder

Did you enjoy this blog? Get more articles like it before anyone else when you subscribe to our monthly newsletter, The Wayfinder.

Sign me up